A Survivor's Story: by David Flynn USN

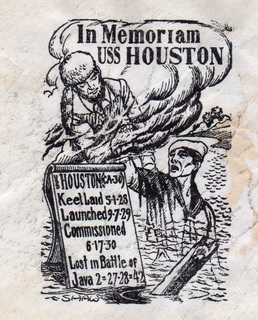

WWII Poster in Memoriam of the USS Houston

lost in the Battle of the Java Sea, in 1942.

This poster lists the ship as lost on February 27-28 of 1942.

The USS Houston fought on until approximately 12:25am

on the morning of March 1, 1942.

Image from the private archives of Mr. David Flynn.

Mr. Flynn was a member of this Museum, he passed away in May 29, 2014.

The following, was related by David Flynn. Condensed from his letters:

“Surviving The Galloping Ghost of the Java Coast.”

David Flynn signed with the US Navy prior to the United States entering WWII. During the war, he served aboard the USS Houston as a Radio man 1st Class. The following is a condensed account of his capture and survival, as a prisoner of war in the hands of the Japanese military:

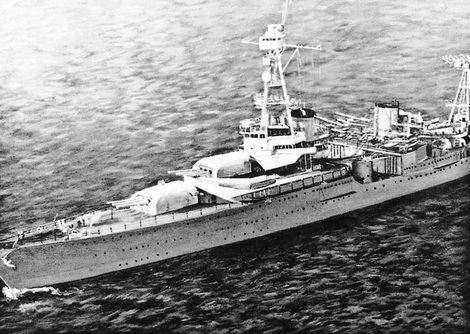

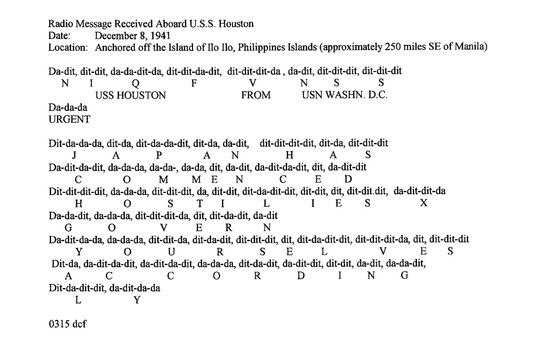

"The USS Houston was a Northampton class heavy cruiser. It was a spit and polish ship, the favorite of President Roosevelt. A special elevator was installed for the president who made 3 world cruises aboard the Houston in 1933, 1935 and 1939. In October 1940, the Houston left for Manila under the command of Captain Albert H. Rooks, to become the flag ship of the Asiatic Fleet. In late 1941, although not yet at war, strict radio silence was maintained. On December 8, 1941 my headphones started buzzing and I typed the incoming message that stated: Japan has commenced hostilities. Govern yourselves accordingly. The message was immediately delivered to Captain Rooks. General quarters were sounded and the Houston got underway hugging the shadows of the mountains. The next several months were spent convoying ships in an attempt to bolster the defenses of Australia and the Netherlands East Indies. Tokyo Rose reported so many times that the Houston had been sunk by the Japanese that she was nicknamed The Galloping Ghost of the Java Coast.

On Feb 3 1942, while operating in the Flores Sea, NE of Java, along with the light cruiser Marblehead, the Houston came under the attack of 49 Japanese bombers. One bomb caused damage leaving the ship without 1/3 of her main battery fire power, killing 48 and wounding 25. On Feb 15, the convoy came under another attack by 50 Japanese aircraft and the Houston valiantly defended the convoy, drawing full attention of the planes. Captain Rooks had developed a technique for avoiding bombs: he'd lie on the deck and some 10 seconds after the planes released their bombs, he would order a hard turn to port or starboard. The bombs would fall harmlessly along the ship. The convoy this time was saved and escorted back to Port Darwin.

"The USS Houston was a Northampton class heavy cruiser. It was a spit and polish ship, the favorite of President Roosevelt. A special elevator was installed for the president who made 3 world cruises aboard the Houston in 1933, 1935 and 1939. In October 1940, the Houston left for Manila under the command of Captain Albert H. Rooks, to become the flag ship of the Asiatic Fleet. In late 1941, although not yet at war, strict radio silence was maintained. On December 8, 1941 my headphones started buzzing and I typed the incoming message that stated: Japan has commenced hostilities. Govern yourselves accordingly. The message was immediately delivered to Captain Rooks. General quarters were sounded and the Houston got underway hugging the shadows of the mountains. The next several months were spent convoying ships in an attempt to bolster the defenses of Australia and the Netherlands East Indies. Tokyo Rose reported so many times that the Houston had been sunk by the Japanese that she was nicknamed The Galloping Ghost of the Java Coast.

On Feb 3 1942, while operating in the Flores Sea, NE of Java, along with the light cruiser Marblehead, the Houston came under the attack of 49 Japanese bombers. One bomb caused damage leaving the ship without 1/3 of her main battery fire power, killing 48 and wounding 25. On Feb 15, the convoy came under another attack by 50 Japanese aircraft and the Houston valiantly defended the convoy, drawing full attention of the planes. Captain Rooks had developed a technique for avoiding bombs: he'd lie on the deck and some 10 seconds after the planes released their bombs, he would order a hard turn to port or starboard. The bombs would fall harmlessly along the ship. The convoy this time was saved and escorted back to Port Darwin.

"Govern yourselves accordingly"

Radio message received on December 8, 1941 by David Flynn aboard the USS Houston.

The Houston at this point was anchored off the Island of Ilo Ilo, Philippines Islands

(approximately 250 miles SE of Manila).

Image © from the private archives of Mr. David Flynn.

The Houston then headed North to join a multinational fleet: the American-British-Dutch-Australian Command known as ABDACOM under the command of Dutch Admiral Doorman. It was at best a ragtag battle group but all that was available to face a superior Japanese task force. On Feb 27, 1942 the two met head-on for what was to be the biggest naval battle since Jutland in WWI and the last time that ships stood toe to toe and fought a traditional surface battle. At the end of over 7 hours of bitter fighting and heavy losses on both sides, only the HMAS Perth and the USS Houston remained and were ordered to head to the western Java Port of Djakarta, refuel and proceed to the southern port of Tjilatjap to evacuate American troops from the island.

We arrived during the early morning of Feb 28th and found the port in complete chaos. The Dutch had already evacuated. The refueling hose had to be jury-rigged to get only a portion of the fuel needed. The Houston and Perth left Djakarta shortly after arriving, confident that we would be able to break through, since Dutch air patrols reported no Japanese naval activity. About 11:00pm just before reaching Sunda Straits at the western end of Java, the Perth sighted and fired upon several Fubuki class Japanese destroyers. Some 55 Japanese transports were already unloading troops. The Houston and Perth sighted a Japanese Task Force. The scene that ensued was utter chaos— shells and torpedoes going in all directions. Survivors later told of seeing many sunken Japanese ships along the shore. Shortly after midnight, the Perth took her fourth torpedo and went down. Houston fought on until approximately 12:25 on the morning of March 1, 1942. She took a fourth torpedo and abandon ship was ordered. I left my battle station in the plotting room, climbed up the inside leg of the main mast and exited at the communication deck. Fires were everywhere.

The Japanese had encircled the Houston, illuminated it with searchlights and were raking the Houston with shells and machine gunfire. An exploding shell killed Captain Rooks. Then some shrapnel hit me. I entered the water with the goal of distancing myself from the ship. The Japanese continued to rake the survivors. I'd swim under water for as long as I could, surface, glance at the Houston and submerge. Finally, the Houston and the Japanese vanished. All was quiet and dark. During the night I met another Houston survivor. We talked for a while and mutually elected to separate. We'd make smaller targets. About noon on March 1st, I was picked up by a Japanese boat and taken to what appeared to be a repair ship. There were four or five other Houston survivors on board. We were given blankets, clothes rung out and my shrapnel wounds attended to. The captain interrogated us, where is the Enterprise, Lexington, etc, etc. We knew nothing. Hours later, the Japanese ship was torpedoed. I went over the side (in haste I put my pants inside-out) and started swimming. I later found myself topside of a Japanese destroyer, along with many Australian survivors. After some time (no food or water), we were transferred to the hold of a Japanese transport— the Sandong Maru where we were held for many days with little food or water. The containers that were used for human refuse also served as food vessels. Men continued to scream and to die. We then were taken to Serang Java.

While the Japanese decided what to do with us, we were made to stand in a destroyed railway station surrounded by many soldiers with fixed bayonets. Eventually, we were herded into a native movie theater. The seats had been removed and the prisoners seated in a cross-legged fashion. It was not possible to lie down. The Japanese manned alcoves and boxes with machine guns. Food was a rarity and consisted of rice and boiling water. Prisoners continued to die. Sanitary facilities consisted of a trench located to the rear of the theater. Flies abounded. My left leg began to swell. A couple of Aussies took me to the Perth's doctor who'd set up shop outside the theater near the latrine trenches. He lanced my leg using a razor blade. Weeks later we were moved to Bicycle Camp in Djakarta. The camp was a staging area for shipment of POW's to Saigon's coalmines, steel mills and shipyards as slave labor. Officers were sent to Manchuria. Selection seemed to be based on physical wellness and was made by a Japanese doctor. Meanwhile, I remained in Java. We were ordered by the Japanese to sign a document stating we'd work for Dai Nippon and would make no attempt to escape, etc. Our officers ordered us not to sign. To do so, would be considered traitorous. The officers were taken away. Every 15 minutes a Japanese bashing squad would come yelling and would beat us with riffle butts and clubs. It was decided between the POW's that this constituted duress and so we signed their piece of paper.

Life settled into a boring routine of work-parties, being sick, and beatings. But life was not completely lacking in levity: a suyakasan (Japanese interpreter) approached me one day. He had a letter from an American patient in a sanatorium. The translator needed help in understanding the letter. (We never received letters). After lamenting his problems for a paragraph or so, the patient went on— say, I'm sure sorry to hear of the fix you're in— he continued, why is a Japanese pilot like a woman's girdle? And then the punch line: A good yank can bring them both down. The interpreter asked: What does this mean? I tried unsuccessfully to explain double-entendre, two meanings and play on words. He finally left muttering, wakardemasen, wakardemasen (I don't understand).

A clandestine radio existed in the camp. The Japanese apparently knew it existed. Searches lasting hours were held at night but they were unsuccessful in locating the radio. Food consisted of red rice (rice with the husks), tea and anything else we were able to scrounge and throw into a pot called groente soep by the Dutch. Food quantities were based on the number of POW's supplied for working parties. The sick had no food allocation. On one occasion, I was offered Java rabbit but that turned out to be cat. Captured pilots held outside the guardhouse were occasionally seen. They would be in bad shape. They would then disappear.

One day, the guards speaking in combination of Malay, Japanese and English, attempted to describe a huge explosion. Although we did not know it at the time, this turned out to be Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In the following days all but a token force of guards vanished. Food and clothing were air dropped. Few were able to eat. The rich food made one sick. The Army Air Corps arrived and took the American POW's to Singapore and then to Calcutta. We remained in a Calcutta army hospital a few weeks. The group I was with, was loaded into a C-54. We made it as far as Karachi and engine trouble forced a transfer to a C-47. Our next stop was Iceland and then on to St. Alban's Hospital in New York.”

We arrived during the early morning of Feb 28th and found the port in complete chaos. The Dutch had already evacuated. The refueling hose had to be jury-rigged to get only a portion of the fuel needed. The Houston and Perth left Djakarta shortly after arriving, confident that we would be able to break through, since Dutch air patrols reported no Japanese naval activity. About 11:00pm just before reaching Sunda Straits at the western end of Java, the Perth sighted and fired upon several Fubuki class Japanese destroyers. Some 55 Japanese transports were already unloading troops. The Houston and Perth sighted a Japanese Task Force. The scene that ensued was utter chaos— shells and torpedoes going in all directions. Survivors later told of seeing many sunken Japanese ships along the shore. Shortly after midnight, the Perth took her fourth torpedo and went down. Houston fought on until approximately 12:25 on the morning of March 1, 1942. She took a fourth torpedo and abandon ship was ordered. I left my battle station in the plotting room, climbed up the inside leg of the main mast and exited at the communication deck. Fires were everywhere.

The Japanese had encircled the Houston, illuminated it with searchlights and were raking the Houston with shells and machine gunfire. An exploding shell killed Captain Rooks. Then some shrapnel hit me. I entered the water with the goal of distancing myself from the ship. The Japanese continued to rake the survivors. I'd swim under water for as long as I could, surface, glance at the Houston and submerge. Finally, the Houston and the Japanese vanished. All was quiet and dark. During the night I met another Houston survivor. We talked for a while and mutually elected to separate. We'd make smaller targets. About noon on March 1st, I was picked up by a Japanese boat and taken to what appeared to be a repair ship. There were four or five other Houston survivors on board. We were given blankets, clothes rung out and my shrapnel wounds attended to. The captain interrogated us, where is the Enterprise, Lexington, etc, etc. We knew nothing. Hours later, the Japanese ship was torpedoed. I went over the side (in haste I put my pants inside-out) and started swimming. I later found myself topside of a Japanese destroyer, along with many Australian survivors. After some time (no food or water), we were transferred to the hold of a Japanese transport— the Sandong Maru where we were held for many days with little food or water. The containers that were used for human refuse also served as food vessels. Men continued to scream and to die. We then were taken to Serang Java.

While the Japanese decided what to do with us, we were made to stand in a destroyed railway station surrounded by many soldiers with fixed bayonets. Eventually, we were herded into a native movie theater. The seats had been removed and the prisoners seated in a cross-legged fashion. It was not possible to lie down. The Japanese manned alcoves and boxes with machine guns. Food was a rarity and consisted of rice and boiling water. Prisoners continued to die. Sanitary facilities consisted of a trench located to the rear of the theater. Flies abounded. My left leg began to swell. A couple of Aussies took me to the Perth's doctor who'd set up shop outside the theater near the latrine trenches. He lanced my leg using a razor blade. Weeks later we were moved to Bicycle Camp in Djakarta. The camp was a staging area for shipment of POW's to Saigon's coalmines, steel mills and shipyards as slave labor. Officers were sent to Manchuria. Selection seemed to be based on physical wellness and was made by a Japanese doctor. Meanwhile, I remained in Java. We were ordered by the Japanese to sign a document stating we'd work for Dai Nippon and would make no attempt to escape, etc. Our officers ordered us not to sign. To do so, would be considered traitorous. The officers were taken away. Every 15 minutes a Japanese bashing squad would come yelling and would beat us with riffle butts and clubs. It was decided between the POW's that this constituted duress and so we signed their piece of paper.

Life settled into a boring routine of work-parties, being sick, and beatings. But life was not completely lacking in levity: a suyakasan (Japanese interpreter) approached me one day. He had a letter from an American patient in a sanatorium. The translator needed help in understanding the letter. (We never received letters). After lamenting his problems for a paragraph or so, the patient went on— say, I'm sure sorry to hear of the fix you're in— he continued, why is a Japanese pilot like a woman's girdle? And then the punch line: A good yank can bring them both down. The interpreter asked: What does this mean? I tried unsuccessfully to explain double-entendre, two meanings and play on words. He finally left muttering, wakardemasen, wakardemasen (I don't understand).

A clandestine radio existed in the camp. The Japanese apparently knew it existed. Searches lasting hours were held at night but they were unsuccessful in locating the radio. Food consisted of red rice (rice with the husks), tea and anything else we were able to scrounge and throw into a pot called groente soep by the Dutch. Food quantities were based on the number of POW's supplied for working parties. The sick had no food allocation. On one occasion, I was offered Java rabbit but that turned out to be cat. Captured pilots held outside the guardhouse were occasionally seen. They would be in bad shape. They would then disappear.

One day, the guards speaking in combination of Malay, Japanese and English, attempted to describe a huge explosion. Although we did not know it at the time, this turned out to be Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In the following days all but a token force of guards vanished. Food and clothing were air dropped. Few were able to eat. The rich food made one sick. The Army Air Corps arrived and took the American POW's to Singapore and then to Calcutta. We remained in a Calcutta army hospital a few weeks. The group I was with, was loaded into a C-54. We made it as far as Karachi and engine trouble forced a transfer to a C-47. Our next stop was Iceland and then on to St. Alban's Hospital in New York.”

Left image: David Flynn at Boot-camp circa 1938. Right image: Letter from President Harry Truman. Images © from the private archives of Mr. David Flynn.

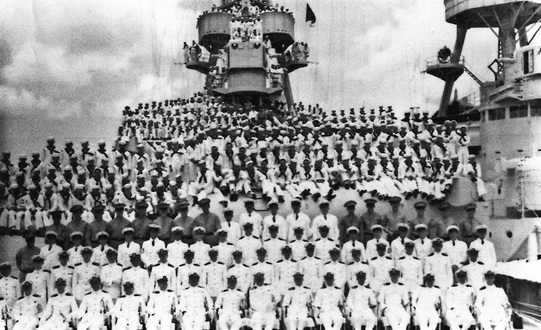

The USS Houston had a crew of 1,015 officers and men. 655 were killed in action, slaughtered in the water or drowned. 360 survived— of these,79 of the crew would die during their 3 1/2 years as prisoners of war. The city of Houston, Texas, upon learning of the loss of the Houston in 1942, held a fund drive, which netted $85,000,000. This was sufficient to build a second USS Houston and a small aircraft carrier— the San Jacinto. One thousand Texans volunteered and signed up to man the ships. Photos: from the private archives of Mr. David Flynn.

Click here to visit the USS Houston CA-30 Survivor's Association & Next Generations Website.

Museum's Books | Memberships | Newsletter | NASFL History | Flight 19 | Memorial | Volunteer | Media Kit

|

Copyright © NAS Fort Lauderdale Museum

For use of images or text please contact webmaster Website created by Moonrisings, August 3, 2010 |