Charles J. Schaus USNR, WWII

USS Barton DD-722

S 1st Class (Fire Controlman)

USS Barton DD-722

S 1st Class (Fire Controlman)

USS Barton DD-722

Charles J. Schaus was born in 1926 in Washington DC. His father was a U.S Army Staff Sergeant serving in France during World War I. Charles comes from a long line of military servicemen, dating back to the war of 1812. On his seventeen birthday he joined the Navy and was assigned to the Gunnery Department and Fire Control, from Aug. 1943 to Feb. 1946 aboard the USS Barton DD-722— a distinguished fighting ship of World War II. Charles participated in D-Day Normandy and the bombardment of Cherbourg. And, later invasions in the Pacific: Luzon in the Philippines, including the battle of Ormac Bay, landings in Mindoro and Lingayen, Iwo Jima and Okinawa. He was also present aboard his ship upon the surrender of Japan.

On one occasion as the Barton headed for the German stronghold at Cherbourg, France, the ship was straddled by the second salvo from the enemy coastal batteries. One 240-millimeter shell skipped off the water’s surface, ripped through the port quarter, and lodged in the after-diesel generator room. Fortunately, the shell failed to detonate, and a repair party jettisoned it quickly. Throughout the war, the USS Barton pursued an exhausting routine. She performed a variety of activities: fire support, anti-aircraft defense, antisubmarine screening during which she sank a midget submarine (unconfirmed), and radar picket duty. Her 5-inch gun barrels nearly wore out as a result of firing over 22,000 rounds— rounds that knocked out 150 enemy emplacements, hit 35 supply dumps, and dispersed 23 troop concentrations. Especially dangerous were the hours spent on radar picket stations, alone, and exposed to deadly kamikaze aerial attacks while operating off Okinawa. One such plane came in so close astern to Barton before being shot down by her anti-aircraft fire, that gasoline fumes were sucked into the destroyer’s ventilation system. Many a time, the crew was placed in precarious situations near the precipice. However, her officers and her men withstood the stress and perils of these hazardous missions, to provide effective Naval gunfire support over the three months of the Okinawa campaign. All this without losing a single man from enemy attacks. “The Luck of the Barton.”

After the war, Charles married and had two sons, one serving in the Army as an MP in Vietnam. Under the GI Bill, Charles graduated in 1951 from the American University in Washington, D.C, with a degree in Business Administration. He then went to work for the Department of the Navy and at the Special Projects Office (Polaris Missile Submarine Development), until 1962. He also served in Federal Civilian Departments, including the National Transportation Safety Board, working as Budget and Fiscal Director, and in the Dept. of Transportation as Senior Budget Examiner in the Office of the Secretary. Charles retired from public service in 1981. He remained very active with the USS Barton Association, and was its President from 1987 to 1996. He currently resides in Florida. Charles has donated several historic artifacts, books and photographs and a model of the USS Barton, which are on display at our Museum.

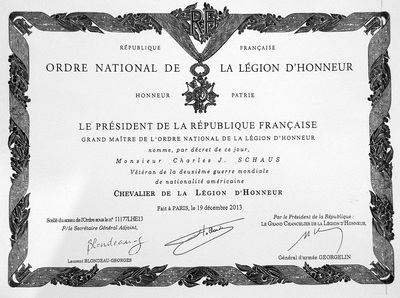

On May 2, 2014, on board the USS New York at Port Everglades in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, the nation of France honored 22 men with the Legion of Honor medals. Among them was WWII Veteran Charles Schaus, who was a sailor aboard the USS Barton DD-722—a distinguished fighting ship of World War II. From 1943 to Feb of 1946, Charles would participate in several battles: in D-Day Normandy and the bombardment of Cherbourg. And later invasions in the Pacific: Luzon, Philippines, including the battle of Ormac Bay, landings in Mindoro and Lingayen, Iwo Jima and Okinawa. He was also present aboard his ship upon the surrender of Japan. The USS Barton never lost a single man. With the Ordre national de la Légion d'honneur medal, the veterans now have the title Knight in the National Order of the Legion of Honor. This is an honor that was created by Napoleon in 1802. Notable Americans who have received the award include: Thomas Edison, Alexander Graham Bell, Dwight D. Eisenhower, and former Secretary of State Colin Powell.

Click on thumbnails to enlarge

HISTORY of the USS BARTON DD-722

Laid down by Bath Iron Works, Bath ME May 24 1943.

Launched: October 10 1943, and commissioned December 30 1943.

Decommissioned: January 22 1947, recommissioned April 11 1949.

Decommissioned and Stricken October 1 1968.

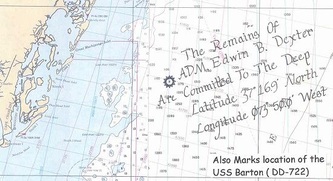

Fate: Sunk as target off Virginia October 8 1969.

The USS Barton during WWII

The USS Barton set out on 14 May 1944, to make her first Atlantic crossing in company with a convoy bound for the British Isles. The destroyer escorted the convoy into Greenock, Scotland on 24 May. The next day, Barton led some transports down the Irish Sea passing the English Channel to Plymouth, England on 27 May. Barton then joined for a rendezvous with the many other units that would make up the invasion task force for Operation “Overlord.” After a postponement of a few days, the assault proceeded to the invasion destinations early on the morning of 6 June. The destroyer received orders to provide gunfire support for troops ashore and carried out such missions during the first four days of the operation. On D-day she rushed to the aid of elements of the Army’s 2nd Ranger Battalion that, after successfully scaling the nearly sheer heights of Pointe du Hoc to capture a six-gun battery, found it was missing. Although the guns had been removed, their crews and supporting troops had not, and they put up quite a stiff resistance that pared down the Rangers’ numbers after a time and placed them in a precarious situation near the precipice. Barton’s guns joined with those of Satterlee (DD 626) and Thompson (DD 627) in keeping the Ranger’s tormentors at bay. She even sent her motor whaleboat shoreward with a pharmacist’s mate and an Army glider to assist the unit’s wounded, but German gunfire thwarted the attempt, wounding the medic and holing the boat in eight places. Though Barton’s whaleboat crew brought no succor to the Ranger wounded, her guns gave a good account of themselves in bolstering the defensive perimeter until the destroyer turned the responsibility over to her relief ship, Thompson.

For the next two weeks, call-fire missions in support of the troops ashore, such as the one she had carried out for the Rangers on Pointe du Hoc, frequently called her away from duty screening transports and the battleship Texas against submarine and aircraft attack. Yet, she managed to make a real contribution to the defense of the invasion fleet as well by helping to ward off air attacks on the 7th and the 11th during the first of which attacks, she claimed to have splashed a JU 88 German bomber. Screening duties and call-fire missions occupied her until mid-morning on 21 June when she left the French coast for Weymouth, England. After a two-day rest at Weymouth, England, Barton got underway on 25 June as part of Task Group (TG) 129.2, heading for the German stronghold at Cherbourg, France. Operating with the battleships and cruisers sent to bombard the port, Barton was straddled by the second salvo from the enemy coastal batteries. One 240-millimeter shell skipped off the water’s surface, ripped through the port quarter, and lodged in the after diesel generator room. Fortunately, the shell failed to detonate, and a repair party jettisoned it quickly. Back in Weymouth, Barton received a temporary patch before getting underway for Belfast, Northern Ireland. There, she joined Destroyer Division (DesDiv) 119 in the voyage to Boston, arriving there on 9 July.

At Boston, the hull puncture was permanently repaired, and Barton returned to sea on 7 September bound for Norfolk, VA. She rendezvoused with Eldorado (AGC 11) at Norfolk and the two ships put to sea, heading for the Panama Canal and into San Diego, where they arrived without incident on 29 September. Barton continued on to Pearl Harbor, arriving there on 8 October to undergo inspection and training. The destroyer got underway on the 23d for Ulithi and arrived there on 5 November. Soon thereafter, Barton assumed duty guarding the carriers of Task Group (TG) 38.4 during air strikes against the Philippines. Screening these ships during air operations kept Barton busy until her return to Ulithi on 21 November. The warship got underway on 27 November in company with Destroyer Squadron (DesRon) 60 to join the Seventh Fleet at Leyte. Barton operated with the screening units until 6 December when she sailed for Ormoc Bay to support a major landing of the 77th Infantry Division. An enemy shore battery opened fire on the ships near dawn on 7 December, but Barton, Laffey (DD 724) and O’Brien (DD 725) quickly demolished the site. Trouble developed as Barton escorted the empty invasion convoy back to Leyte. Japanese aircraft attacked the convoy using kamikaze tactics. One plane came in so close astern to Barton before being shot down by her antiaircraft fire that gasoline fumes were sucked into the destroyer’s ventilation system. A rainstorm moved in to cover the convoy’s track, but the enemy persevered, and Barton assisted in splashing another plane before the unit arrived at San Pedro Bay on 8 December.

In anticipation of landing at Lingayen Gulf, the Allies planned to seize Mindoro Island to establish close-range airfields. Barton became part of the support force off Mindoro when the invasion began on 15 December and met negligible opposition. The destroyer saw little action, but did sight and sink a small Japanese coastal freighter with Ingraham’s (DD 694) help. The ships returned to San Pedro Bay on 17 December. Barton spent Christmas at Leyte while plans moved forward for the invasion of Luzon at Lingayen Gulf. The destroyer stood out of San Pedro Bay on 2 January 1945 to join TG 77.2. Late on 5 January, Barton stood off the entrance to the entrance to the Gulf. The next day the Allen M. Summer (DD-692) and Walke (DD-723) suffered hits by Kamikazes while covering minesweepers. The Barton and O'Brien relieved them. One Kamikaze crashed O’Brien’s port side and two others fell to Barton’s guns. Barton then relieved the O’Brien to escort a group of minesweepers safely into the Gulf. O’Brien’s Commander, W.W. Outerbridge wrote …”Her task was the most hazardous I have ever seen a vessel undertake” from History of Naval Operations in WW-II By Samuel Eliot Morison. On 7 January Barton and the Leutze (DD-481) collaborated in sinking an enemy patrol craft. The two warships then returned to screening duties until the amphibious assault went forward on the 9th, at which point she aided call-fire missions in support of the troops ashore to her list of chores. Barton remained on call at Lingayen until late January, helping to bring down one more enemy plane during her stay.

On 22 January, she received orders to retire to Ulithi and arrived there six days later. The destroyer was immediately assigned as a screening unit for the carriers of TG 58.4, scheduled for air strikes against Tokyo as diversionary tactics for the landing on Iwo Jima. Barton was cruising the waters off Honshu on 16 February when the first planes left the carriers. Late that night, while patrolling within 100 miles of Japan, Barton and Ingraham collided, bending and tearing Barton’s bow and destroying Ingraham’s starboard 40-millimeter gun mount. Escorted by Moale (DD 693), the two disabled ships set course for Saipan. At 2115 on 17 February, Barton picked up two contacts on her radar, and the trio of destroyers closed to attack. Their guns made quick work of the two enemy guardboats the warships had flushed. Before dawn the next morning, she her radar picked up another Japanese guardboat which the three warships also promptly dispatched with gunfire. Barton and her companions reached Saipan on 20 February and began repairs. Ingraham completed repairs in three days and returned to action, but Barton required considerably more attention. On the 23rd, she entered the drydock at Guam to have her bow rebuilt. On 15 March, the rejuvenated warship stood out for Ulithi, arriving the next day to prepare for the upcoming assault on Okinawa in the Ryukyus. Misfortune struck on 20 March, however, while a group of her sailors refuzed projectiles on the forecastle. One shell began smoking, spewing white phosphorous, and Chief Gunners Mate King tossed the shell over the side before it completely exploded, but badly burned, he succumbed to his injury in the US. Three officers and 11 enlisted men suffered burns and remained behind when Barton left Ulithi on 21 March.

Five days later, on 26 March, the destroyer joined in the pre-invasion bombardment of Okinawa. Enemy air activity grew intense throughout the following weeks, and Barton became a frequent target of the suicide planes. On 27 March, she shot down one enemy bomber and assisted in splashing another, and two days later repeated the scenario of one kill and one assist. The troops hit Okinawa’s beaches on 1 April. Meanwhile, Barton attacked a Japanese midget submarine with depth charges and claimed probable damage to it. On 6 April, she scored another aerial kill and tallied an additional assist on the 9th. Day and night for three months, the destroyer pursued an exhausting routine. She performed a variety of activities: fire support, antiaircraft defense, antisubmarine screening, and radar picket duty. Her 5-inch gun barrels nearly wore out as a result of firing over 22,000 rounds of 5" ammunition that knocked out 150 enemy emplacements, hit 35 supply dumps, and dispersed 23 troop concentrations. Especially dangerous were the hours spent on radar picket stations, alone and open to attack from enemy submarines, torpedo boats, and aircraft. Destroyers manning these hazardous positions were all too often replaced rather than relieved, but Barton survived and saw the end of organized resistance on Okinawa on 21 June.

The Barton then steamed to Kerama Retto to refuel and load supplies before joining Vice Admiral Jesse B. Oldendorf’s TF 95 for an anti-shipping sweep in the East China Sea and the Yellow Sea. At the conclusion of that mission, Barton shaped a course for Leyte on 23 July, joining a hunter-killer group en route in a fruitless search for Japanese midget submarines. The submarines had attacked destroyer escort Underhill (DE 682) and then lurked nearby to interfere with efforts to rescue the crew of the sinking ship. Barton stood into Leyte Gulf on 29 July for an availability period and was there on 15 August to receive the news of Japan’s capitulation. She received orders to embark the New Zealand government representative, Air Vice Marshall Isitt, at Iwo Jima and to transport him to Missouri (BB 63) for the formal surrender ceremony. While the actual ceremony was in progress, and for two weeks thereafter, Barton operated with the covering carrier task force in the vicinity of Tokyo Bay. On 16 September, she anchored inside Tokyo Bay for a brief rest before returning to Okinawa. There, the destroyer embarked returning soldiers and set out for the west coast of the United States, arriving in Seattle on 19 October. Barton observed Navy Day in Everett, Washington, then sailed for San Francisco on 31 October and remained in that port for several months’ stand down and repair. She then conducted training in preparation for her next assignment, duty as a surface survey ship during the atomic bomb tests at Bikini Atoll. Early in June, after the installation of special oceanographic and radiological equipment, Barton got underway and headed for the central Pacific. She stopped at Pearl Harbor on the 8th and then at Kwajalein on the 13th, joining the eight other destroyers that formed the surface patrol unit of Joint TF 1. On 15 June, Barton arrived at Bikini Atoll, and preparations moved forward for the two nuclear tests. At 0900 on 1 July, the ship observed the first event, Test “Able,” from a distance of between 11.7 and 15 miles from ground zero. At 0944, Barton proceeded to the lagoon entrance to survey the radiological effects. She then took oceanographic soundings until anchoring in the lagoon early the next morning to record data gathered there. For the next three weeks, Barton moved through the test area monitoring radiation levels and accumulating other data. At 0835 on 25 July, Barton observed Test “Baker” from a distance of between eight to 10 miles from surface zero. At 0900, the ship began a radiological patrol of the waters including the area just inside the lagoon entrance, before beginning 12 days of soundings and readings. On 5 August, the destroyer conducted calibration firing exercises and gunfire drills before departing for San Diego, where she arrived on 22 August. Barton was readied for inactive status and on 22 January 1947, was placed out of commission, in reserve, at San Diego. Barton was recommissioned on 11 April 1949, Comdr. Charles W. Rush, Jr., in command. She served as a unit of DesDiv 201 in local operations along the west coast until 11 July when she embarked upon the voyage to a new assignment, as a unit of the Atlantic Fleet.

WWII - COMMENDATION

THE SECRETARY OF THE NAVY

WASHINGTON

The President of the United States takes pleasure in commending the

UNITED STATES SHIP BARTON

for service as follows:

“For outstanding heroism in action as a Fire Support Ship and as Radar Picket Ship during the Okinawa Campaign, from March 21 to June 30, 1945. A natural and frequent target for heavy Japanese aerial and submarine attack while operating off Okinawa, the U.S.S. BARTON defeated all efforts of the enemy to destroyer her. Constantly vigilant and ready for battle, she rendered invaluable service in providing fire support, as a part of the anti-submarine and antiaircraft screens, as a unit of the anti-suicide-boat and anti-small-boat patrols, and as radar picket ship, inflicting heavy damage on enemy material and personnel. With her own gunfire, she downed four hostile planes, assisted in the destruction of four others and sank one enemy midget submarine. A gallant, fighting ship, the BARTON, her officers and her men withstood the stress and perils of these hazardous missions to provide effective Naval gunfire support for our ground operations on Okinawa, achieving a distinctive combat record which attests the teamwork, courage and skill of her entire company and enhances the finest traditions of the United States Naval Service.”

All personnel attached to and serving on board the U.S.S. BARTON from March 21 to June 30, 1945,

are authorized to wear the NAVY UNIT COMMENDATION Ribbon.

Secretary of the Navy

World War II - SERVICE STARS

Barton earned six bronze service stars:

one on her European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Ribbon and five on her Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Ribbon as follows:

1 Star: INVASION OF NORMANDY

6–25 June 1944

1 Star: LEYTE OPERATION

Luzon attacks: 13–19 November 1944

Ormoc Bay landings: 7–8 December 1944

1 Star: LUZON OPERATION

Mindoro landings, 12–18 December 1944

Lingayen Gulf landing, 4–18 January 1945

1 Star: IWO JIMA OPERATION

Assault and occupation of Iwo Jima: 10–17 February 1945

Fifth Fleet raids against Honshu and Nansei Shoto: 15 February–1 March 1945

1 Star: OKINAWA OPERATION

Assault and occupation of Okinawa: 25 March–30 June 1945

1 Star: THIRD FLEET OPERATIONS AGAINST JAPAN

10 July–15 August 1945

Launched: October 10 1943, and commissioned December 30 1943.

Decommissioned: January 22 1947, recommissioned April 11 1949.

Decommissioned and Stricken October 1 1968.

Fate: Sunk as target off Virginia October 8 1969.

The USS Barton during WWII

The USS Barton set out on 14 May 1944, to make her first Atlantic crossing in company with a convoy bound for the British Isles. The destroyer escorted the convoy into Greenock, Scotland on 24 May. The next day, Barton led some transports down the Irish Sea passing the English Channel to Plymouth, England on 27 May. Barton then joined for a rendezvous with the many other units that would make up the invasion task force for Operation “Overlord.” After a postponement of a few days, the assault proceeded to the invasion destinations early on the morning of 6 June. The destroyer received orders to provide gunfire support for troops ashore and carried out such missions during the first four days of the operation. On D-day she rushed to the aid of elements of the Army’s 2nd Ranger Battalion that, after successfully scaling the nearly sheer heights of Pointe du Hoc to capture a six-gun battery, found it was missing. Although the guns had been removed, their crews and supporting troops had not, and they put up quite a stiff resistance that pared down the Rangers’ numbers after a time and placed them in a precarious situation near the precipice. Barton’s guns joined with those of Satterlee (DD 626) and Thompson (DD 627) in keeping the Ranger’s tormentors at bay. She even sent her motor whaleboat shoreward with a pharmacist’s mate and an Army glider to assist the unit’s wounded, but German gunfire thwarted the attempt, wounding the medic and holing the boat in eight places. Though Barton’s whaleboat crew brought no succor to the Ranger wounded, her guns gave a good account of themselves in bolstering the defensive perimeter until the destroyer turned the responsibility over to her relief ship, Thompson.

For the next two weeks, call-fire missions in support of the troops ashore, such as the one she had carried out for the Rangers on Pointe du Hoc, frequently called her away from duty screening transports and the battleship Texas against submarine and aircraft attack. Yet, she managed to make a real contribution to the defense of the invasion fleet as well by helping to ward off air attacks on the 7th and the 11th during the first of which attacks, she claimed to have splashed a JU 88 German bomber. Screening duties and call-fire missions occupied her until mid-morning on 21 June when she left the French coast for Weymouth, England. After a two-day rest at Weymouth, England, Barton got underway on 25 June as part of Task Group (TG) 129.2, heading for the German stronghold at Cherbourg, France. Operating with the battleships and cruisers sent to bombard the port, Barton was straddled by the second salvo from the enemy coastal batteries. One 240-millimeter shell skipped off the water’s surface, ripped through the port quarter, and lodged in the after diesel generator room. Fortunately, the shell failed to detonate, and a repair party jettisoned it quickly. Back in Weymouth, Barton received a temporary patch before getting underway for Belfast, Northern Ireland. There, she joined Destroyer Division (DesDiv) 119 in the voyage to Boston, arriving there on 9 July.

At Boston, the hull puncture was permanently repaired, and Barton returned to sea on 7 September bound for Norfolk, VA. She rendezvoused with Eldorado (AGC 11) at Norfolk and the two ships put to sea, heading for the Panama Canal and into San Diego, where they arrived without incident on 29 September. Barton continued on to Pearl Harbor, arriving there on 8 October to undergo inspection and training. The destroyer got underway on the 23d for Ulithi and arrived there on 5 November. Soon thereafter, Barton assumed duty guarding the carriers of Task Group (TG) 38.4 during air strikes against the Philippines. Screening these ships during air operations kept Barton busy until her return to Ulithi on 21 November. The warship got underway on 27 November in company with Destroyer Squadron (DesRon) 60 to join the Seventh Fleet at Leyte. Barton operated with the screening units until 6 December when she sailed for Ormoc Bay to support a major landing of the 77th Infantry Division. An enemy shore battery opened fire on the ships near dawn on 7 December, but Barton, Laffey (DD 724) and O’Brien (DD 725) quickly demolished the site. Trouble developed as Barton escorted the empty invasion convoy back to Leyte. Japanese aircraft attacked the convoy using kamikaze tactics. One plane came in so close astern to Barton before being shot down by her antiaircraft fire that gasoline fumes were sucked into the destroyer’s ventilation system. A rainstorm moved in to cover the convoy’s track, but the enemy persevered, and Barton assisted in splashing another plane before the unit arrived at San Pedro Bay on 8 December.

In anticipation of landing at Lingayen Gulf, the Allies planned to seize Mindoro Island to establish close-range airfields. Barton became part of the support force off Mindoro when the invasion began on 15 December and met negligible opposition. The destroyer saw little action, but did sight and sink a small Japanese coastal freighter with Ingraham’s (DD 694) help. The ships returned to San Pedro Bay on 17 December. Barton spent Christmas at Leyte while plans moved forward for the invasion of Luzon at Lingayen Gulf. The destroyer stood out of San Pedro Bay on 2 January 1945 to join TG 77.2. Late on 5 January, Barton stood off the entrance to the entrance to the Gulf. The next day the Allen M. Summer (DD-692) and Walke (DD-723) suffered hits by Kamikazes while covering minesweepers. The Barton and O'Brien relieved them. One Kamikaze crashed O’Brien’s port side and two others fell to Barton’s guns. Barton then relieved the O’Brien to escort a group of minesweepers safely into the Gulf. O’Brien’s Commander, W.W. Outerbridge wrote …”Her task was the most hazardous I have ever seen a vessel undertake” from History of Naval Operations in WW-II By Samuel Eliot Morison. On 7 January Barton and the Leutze (DD-481) collaborated in sinking an enemy patrol craft. The two warships then returned to screening duties until the amphibious assault went forward on the 9th, at which point she aided call-fire missions in support of the troops ashore to her list of chores. Barton remained on call at Lingayen until late January, helping to bring down one more enemy plane during her stay.

On 22 January, she received orders to retire to Ulithi and arrived there six days later. The destroyer was immediately assigned as a screening unit for the carriers of TG 58.4, scheduled for air strikes against Tokyo as diversionary tactics for the landing on Iwo Jima. Barton was cruising the waters off Honshu on 16 February when the first planes left the carriers. Late that night, while patrolling within 100 miles of Japan, Barton and Ingraham collided, bending and tearing Barton’s bow and destroying Ingraham’s starboard 40-millimeter gun mount. Escorted by Moale (DD 693), the two disabled ships set course for Saipan. At 2115 on 17 February, Barton picked up two contacts on her radar, and the trio of destroyers closed to attack. Their guns made quick work of the two enemy guardboats the warships had flushed. Before dawn the next morning, she her radar picked up another Japanese guardboat which the three warships also promptly dispatched with gunfire. Barton and her companions reached Saipan on 20 February and began repairs. Ingraham completed repairs in three days and returned to action, but Barton required considerably more attention. On the 23rd, she entered the drydock at Guam to have her bow rebuilt. On 15 March, the rejuvenated warship stood out for Ulithi, arriving the next day to prepare for the upcoming assault on Okinawa in the Ryukyus. Misfortune struck on 20 March, however, while a group of her sailors refuzed projectiles on the forecastle. One shell began smoking, spewing white phosphorous, and Chief Gunners Mate King tossed the shell over the side before it completely exploded, but badly burned, he succumbed to his injury in the US. Three officers and 11 enlisted men suffered burns and remained behind when Barton left Ulithi on 21 March.

Five days later, on 26 March, the destroyer joined in the pre-invasion bombardment of Okinawa. Enemy air activity grew intense throughout the following weeks, and Barton became a frequent target of the suicide planes. On 27 March, she shot down one enemy bomber and assisted in splashing another, and two days later repeated the scenario of one kill and one assist. The troops hit Okinawa’s beaches on 1 April. Meanwhile, Barton attacked a Japanese midget submarine with depth charges and claimed probable damage to it. On 6 April, she scored another aerial kill and tallied an additional assist on the 9th. Day and night for three months, the destroyer pursued an exhausting routine. She performed a variety of activities: fire support, antiaircraft defense, antisubmarine screening, and radar picket duty. Her 5-inch gun barrels nearly wore out as a result of firing over 22,000 rounds of 5" ammunition that knocked out 150 enemy emplacements, hit 35 supply dumps, and dispersed 23 troop concentrations. Especially dangerous were the hours spent on radar picket stations, alone and open to attack from enemy submarines, torpedo boats, and aircraft. Destroyers manning these hazardous positions were all too often replaced rather than relieved, but Barton survived and saw the end of organized resistance on Okinawa on 21 June.

The Barton then steamed to Kerama Retto to refuel and load supplies before joining Vice Admiral Jesse B. Oldendorf’s TF 95 for an anti-shipping sweep in the East China Sea and the Yellow Sea. At the conclusion of that mission, Barton shaped a course for Leyte on 23 July, joining a hunter-killer group en route in a fruitless search for Japanese midget submarines. The submarines had attacked destroyer escort Underhill (DE 682) and then lurked nearby to interfere with efforts to rescue the crew of the sinking ship. Barton stood into Leyte Gulf on 29 July for an availability period and was there on 15 August to receive the news of Japan’s capitulation. She received orders to embark the New Zealand government representative, Air Vice Marshall Isitt, at Iwo Jima and to transport him to Missouri (BB 63) for the formal surrender ceremony. While the actual ceremony was in progress, and for two weeks thereafter, Barton operated with the covering carrier task force in the vicinity of Tokyo Bay. On 16 September, she anchored inside Tokyo Bay for a brief rest before returning to Okinawa. There, the destroyer embarked returning soldiers and set out for the west coast of the United States, arriving in Seattle on 19 October. Barton observed Navy Day in Everett, Washington, then sailed for San Francisco on 31 October and remained in that port for several months’ stand down and repair. She then conducted training in preparation for her next assignment, duty as a surface survey ship during the atomic bomb tests at Bikini Atoll. Early in June, after the installation of special oceanographic and radiological equipment, Barton got underway and headed for the central Pacific. She stopped at Pearl Harbor on the 8th and then at Kwajalein on the 13th, joining the eight other destroyers that formed the surface patrol unit of Joint TF 1. On 15 June, Barton arrived at Bikini Atoll, and preparations moved forward for the two nuclear tests. At 0900 on 1 July, the ship observed the first event, Test “Able,” from a distance of between 11.7 and 15 miles from ground zero. At 0944, Barton proceeded to the lagoon entrance to survey the radiological effects. She then took oceanographic soundings until anchoring in the lagoon early the next morning to record data gathered there. For the next three weeks, Barton moved through the test area monitoring radiation levels and accumulating other data. At 0835 on 25 July, Barton observed Test “Baker” from a distance of between eight to 10 miles from surface zero. At 0900, the ship began a radiological patrol of the waters including the area just inside the lagoon entrance, before beginning 12 days of soundings and readings. On 5 August, the destroyer conducted calibration firing exercises and gunfire drills before departing for San Diego, where she arrived on 22 August. Barton was readied for inactive status and on 22 January 1947, was placed out of commission, in reserve, at San Diego. Barton was recommissioned on 11 April 1949, Comdr. Charles W. Rush, Jr., in command. She served as a unit of DesDiv 201 in local operations along the west coast until 11 July when she embarked upon the voyage to a new assignment, as a unit of the Atlantic Fleet.

WWII - COMMENDATION

THE SECRETARY OF THE NAVY

WASHINGTON

The President of the United States takes pleasure in commending the

UNITED STATES SHIP BARTON

for service as follows:

“For outstanding heroism in action as a Fire Support Ship and as Radar Picket Ship during the Okinawa Campaign, from March 21 to June 30, 1945. A natural and frequent target for heavy Japanese aerial and submarine attack while operating off Okinawa, the U.S.S. BARTON defeated all efforts of the enemy to destroyer her. Constantly vigilant and ready for battle, she rendered invaluable service in providing fire support, as a part of the anti-submarine and antiaircraft screens, as a unit of the anti-suicide-boat and anti-small-boat patrols, and as radar picket ship, inflicting heavy damage on enemy material and personnel. With her own gunfire, she downed four hostile planes, assisted in the destruction of four others and sank one enemy midget submarine. A gallant, fighting ship, the BARTON, her officers and her men withstood the stress and perils of these hazardous missions to provide effective Naval gunfire support for our ground operations on Okinawa, achieving a distinctive combat record which attests the teamwork, courage and skill of her entire company and enhances the finest traditions of the United States Naval Service.”

All personnel attached to and serving on board the U.S.S. BARTON from March 21 to June 30, 1945,

are authorized to wear the NAVY UNIT COMMENDATION Ribbon.

Secretary of the Navy

World War II - SERVICE STARS

Barton earned six bronze service stars:

one on her European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Ribbon and five on her Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Ribbon as follows:

1 Star: INVASION OF NORMANDY

6–25 June 1944

1 Star: LEYTE OPERATION

Luzon attacks: 13–19 November 1944

Ormoc Bay landings: 7–8 December 1944

1 Star: LUZON OPERATION

Mindoro landings, 12–18 December 1944

Lingayen Gulf landing, 4–18 January 1945

1 Star: IWO JIMA OPERATION

Assault and occupation of Iwo Jima: 10–17 February 1945

Fifth Fleet raids against Honshu and Nansei Shoto: 15 February–1 March 1945

1 Star: OKINAWA OPERATION

Assault and occupation of Okinawa: 25 March–30 June 1945

1 Star: THIRD FLEET OPERATIONS AGAINST JAPAN

10 July–15 August 1945

Museum's Books | Memberships | Newsletter | NASFL History | Flight 19 | Memorial | Volunteer | Media Kit

|

Copyright © NAS Fort Lauderdale Museum

For use of images or text please contact webmaster Website created by Moonrisings, August 3, 2010 |